Animal skins have been widely used as a writing surface in many cultures, since very ancient times. Leather is known to have been produced in Egypt since, at least, the fourth dynasty. Leather production would become an important and large industry in many places throughout the ancient world. It was produced for both domestic consumption and for export. Leather was used for many different purposes, including the making of footwear, armor, clothing, and as a writing material.

Skins intended for use as a writing surface would, after being cleaned and tanned, have one face carefully prepared and smoothed. Generally, leather was only written on one side. The traditional method of tanning leather used quick-lime. This produced a dry and semi-flexible leather. The Persians developed a tanning process using dates. This process produced a soft and much more flexible product which was highly prized in the ancient world. This improved method of tanning would eventually be used throughout the Arab world.

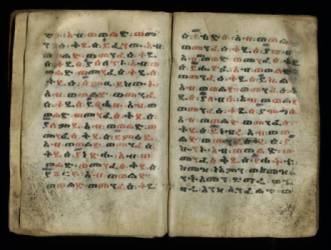

Leather would also play an important part in the coverings of books. The introduction, of the codex or bound form of the book in the early seventh century, produced a need for protective covers for book pages. Some of the earliest book covers were made from leather over a core of thin wood or papyrus mâché. The leather was often decorated with various worked designs. Simple incised parallel lines, punched designs, decorative painting, gilded punched lines, painted decorations and sometimes even colored leathers were used. The more elaborate decorations were generally reserved for important sacred or special works.

In Egypt, during early Islamic times, the Coptic monasteries were well-known for their book binding. Moslem residents would frequently have their books bound at their local Coptic monastery's bindery. Over the successive centuries, leather book-binding would reach great artistic heights in both the East and West. Leather would continue to be used to bind books on a regular basis well into the early twentieth century.

Beginning around the second century B.C.E., a new technique in leather processing produced a writing material which was far superior to leather. It was thin and strong and could be written on both sides. This new material was called parchment and would become the staple writing material of the Middle Ages, especially in Europe.

Parchment was produced by washing liming, stretching and scraping animal skins. Rubbing with pumice and whitening with chalk completed the processing and produced a smooth, thin writing material. The skins from sheep, goats, and calves were most frequently used. The finest parchment was called vellum and was made from the skins of calves and kids. Also, the skins of newly-born or still-born calves and goats were especially prized for use in making the finest and most delicate parchments. Today, the terms parchment and vellum are often used interchangeably. The word parchment is derived from the name of the Greek city of Pergamon (today's Bergama in Turkey) which was a main center of production and traditionally considered to be the place where it was first made.

Parchment, like leather, was used to make scrolls, however, parchment lent itself best to the codex form of book. The Romans used parchment tablets and possibly small "notebooks" for writing drafts and notes. To protect fragile papyrus scrolls while being handled, the Romans made covers out of parchment. These covers were called paenula and were often brightly colored. In addition, a small parchment strip, called a titulus or index, was attached to each scroll. These strips carried the title of the work and were also brightly colored.

Parchment had many advantages, especially over papyrus. It was stronger and more durable than fragile papyrus and the raw-materials for making it, animal skins, were available everywhere and not limited to one geographic location, namely Egypt. Parchment could be written on both sides and if necessary, the writing could be erased (which could also be a disadvantage). Parchment also made an ideal surface for painting. The color of parchment ranged from white and off-white to varying shades of yellow. Expensive colored parchments of blue, purple, and scarlet were also produced, though their use was generally limited to royal or very important and expensive manuscripts.

The main disadvantages of parchment were its cost and limited supply. The raising and up-keep of the animals, their slaughter, and the labor-intensive manufacturing process made it costly and limited how quickly it could be produced. At times, it could not always be produced quick enough and in sufficient quantities to meet demand. Despite the limitations, large quantities were still produced.

During

early Islamic times, parchment would replace papyrus as the preferred material

used in important government and royal documents, land grants, and other legal

documents. Starting in the tenth century, paper would

quickly replace all other types of writing materials to become the dominant writing material among the Arab

peoples. However, for many years, the material of choice for

copying the Qur'an and important literary and scientific works remained

parchment. During this same time period in Europe, the difficulty

in obtaining papyrus and the adoption of the codex as the preferred

book form, enabled parchment to become the dominate writing material

throughout the Middle Ages. It will eventually be superceded by

paper, but would continue be used on a regular basis throughout Europe, especially

for legal documents, well into the 1700's.

During

early Islamic times, parchment would replace papyrus as the preferred material

used in important government and royal documents, land grants, and other legal

documents. Starting in the tenth century, paper would

quickly replace all other types of writing materials to become the dominant writing material among the Arab

peoples. However, for many years, the material of choice for

copying the Qur'an and important literary and scientific works remained

parchment. During this same time period in Europe, the difficulty

in obtaining papyrus and the adoption of the codex as the preferred

book form, enabled parchment to become the dominate writing material

throughout the Middle Ages. It will eventually be superceded by

paper, but would continue be used on a regular basis throughout Europe, especially

for legal documents, well into the 1700's.

European manuscripts written during the fifth and sixth centuries often employed a finely made delicate vellum which was firm and had a smooth glossy surface. After the sixth century, the overall quality of vellum began to gradually decline, due to an ever increasing demand. Over time, regional preferences developed. In Italy, southern France and Greece, vellum with a highly polished glossy surface was the norm. Unfortunately, this type of surface was not very absorbent and frequently resulted in both ink and paint flaking off over time. England, France and Northern Europe preferred a softer and more absorbent vellum. Pure white and extremely fine vellum was popular in Italy during the Renaissance.

Vellum

was also commonly used in bookbinding.. It could be used to cover

a wooden or cardboard core or alone without any backing. Many vellum

bindings are simple and undecorated. Vellum

was often used to cover less-valuable or common books.

However, it could be decorated in a number of ways. Blind stamping or

impressing a design into wet vellum (or leather) with a hot punch or roller

was a common way of decorating vellum bound books. Sometimes it (or the

designs) was also gilded. One decorative technique, invented in the late 18th

century, involved the use of very thin and transparent vellum. A scenic picture,

coat of arms, portrait, or other design would be painted on the underside of the transparent

vellum. This protected the painting from smudging or damage from

handling. The binding would also be decorated with blind stamped and

gilded decorations. This type of binding, named after the family of

booksellers/binders that created and sold them, is known as a 'Halifax'

binding . Because vellum was expensive, it was not uncommon

for old manuscript pages to be reused to make bindings. A number of valuable

and important manuscripts have been recovered from old bindings.

Vellum

was also commonly used in bookbinding.. It could be used to cover

a wooden or cardboard core or alone without any backing. Many vellum

bindings are simple and undecorated. Vellum

was often used to cover less-valuable or common books.

However, it could be decorated in a number of ways. Blind stamping or

impressing a design into wet vellum (or leather) with a hot punch or roller

was a common way of decorating vellum bound books. Sometimes it (or the

designs) was also gilded. One decorative technique, invented in the late 18th

century, involved the use of very thin and transparent vellum. A scenic picture,

coat of arms, portrait, or other design would be painted on the underside of the transparent

vellum. This protected the painting from smudging or damage from

handling. The binding would also be decorated with blind stamped and

gilded decorations. This type of binding, named after the family of

booksellers/binders that created and sold them, is known as a 'Halifax'

binding . Because vellum was expensive, it was not uncommon

for old manuscript pages to be reused to make bindings. A number of valuable

and important manuscripts have been recovered from old bindings.

The high cost of parchment led, not only to the reuse of pages from old, unwanted or damaged manuscripts as materials for bindings, but to the reusing of the pages for writing new manuscripts. The text would be erased by scraping or washing and the clean blank page used to write a new text. The term generally used to describe these twice-used manuscripts is palimpsests. In Arabic, the term tiris, is used to refer to parchment where the original text has been washed off and then reused.

The decline of the classical world and the increasing dominance of Christianity and monasticism in the Middle Ages, lead to the the destruction of many works of classical writers. It was not unusual for a classical text to be obliterated, so the manuscript's pages could be reused for the works of a church Father or grammatical work. This destruction has unintentionally led to the preservation and later recovery of a number of important and previously lost works. Over time, these "erased" texts would often reappear and become visible under the newer text. One famous example is the Codex Ephrami. It preserves portions of a fifth century Biblical text under a twelfth century copy of the works of Ephraem Syrus. Palimpsest manuscripts are not exclusively limited to parchment, papyrus examples are also known.

These erased texts are often difficult to read. In the past, aside from good eyesight, using a magnifying lens, holding the manuscript page up to a light and in some cases, the use of ammonia based compounds to help bring out the underwriting, were the only techniques available to decipher the underwriting. Today, infrared photography, special microscopes and computers have greatly improved the ability of researchers to examine and read the underwriting. Infrared photography and special scanning microscopes can make a nearly invisible text visible. Computer imaging can be used to manipulate the images to further enhance the underwriting and even remove the overwriting altogether.