During the winter of 1889/90, the famous Egyptologist, Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie, was excavating at a site called Gurob. This was an ancient town located near the eastern entrance to the Fayum region in Egypt. At the northern edge of the town was an extensive cemetery dating from Ptolemaic times.

When Petrie excavated the cemetery, he found that the dead had been buried in unpainted, crudely constructed coffins of rough, thin, dark brown wood. Their only decorative feature was a simple carved wooden mask-like face which was attached to the coffin lid by pegs. These masks had triangular noses, holes for eyes, and a slit for a mouth. Occasionally, some of the masks were highlighted with painted eyes. However, these crude and unattractive coffins contained mummies which, though few possessed any ornaments or amulets, were decorated with, often elaborate and colorfully painted, mummy cases made out of cartonnage.

Cartonnage is a type of cardboard-like material. It was used by the ancient Egyptians in a manner similar to how we would use papier-mâché today. It was constructed from layers of linen which had been moistened and stuck together using a kind of paste. This was then coated with a layer of stucco (lime plaster or gesso). It would then be molded into various shapes and left to dry. When it had dried it could then be painted or gilded.

During late Pharonic times, cartonnage was used to make the inner coffins for mummies. It was molded to the shape of the body, forming a one-piece shell. These coffins were often highly decorated with various geometric designs, an assortment of deities and inscriptions, which included verses from the Book of the Dead. The process, of creating an entire mummiform coffin out of cartonnage, was a time consuming and expensive process. During Ptolemaic times, a new, simpler method of mummy decoration would be adopted. Instead of encasing the mummy in a one-piece mummiform shell, it would be covered with four to six separate pieces of decorated cartonnage. These would be attached to the outer mummy wrappings and could easily be mass produced. These separate sections of cartonnage consisted of a mask covering the head and shoulders, a pectoral, an apron for the legs and a foot casing. Sometimes, two additional pieces were added to cover the ribcage and stomach.

The head mask was constructed by molding the cartonnage over a three-dimensional two-piece wood block mold. The back piece of the mold was smooth and would easily slide out when the cartonnage was dry. This would allow the front part, with the facial features, to be easily lifted out. The faces of these masks were often gilded. The earlier masks have facial features similar to those found on the Pharonic coffins and sometimes feature a winged vulture or scarab on the top of the head. The later examples were more life-like and even show the hair styles and jewelry of the time.

The Pectoral or collarplate was generally semicircular shaped. It often imitated a weswkh collar with its strands of beads and falcon terminals. These were painted in bright colors or sometimes completely gilt.

The rectangular apron which covered the legs was often decorated with the four genii (Duamutef, Qebhsenuef, Hapy and Imsety) and occasionally Isis and Nebhat. Sometimes, the famous scene depicting Anubes performing the funeral rites over the mummy was also added.

The foot case covered the feet and ankles. It was decorated on top with sandaled feet and on the bottom with sandal soles. Additionally, cartonnage sandal soles were often placed on the bottom of a mummy’s feet inside the bandages.

The cartonnage pieces which covered the ribcage and stomach often depicted the winged ba bird. These sections would often be cut to the shape of the figure. Sometimes, the image of a winged scarab was also depicted. On some of these pieces, a small, generally square section of the cartonnage would be left undecorated or painted a neutral color. This space was intended for an inscription bearing the name of the deceased. Often, this was never added.

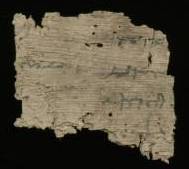

When Petrie examined the cartonnages found on the mummies of Gurob, he found, to his surprise, that the cartonnages were not made from layers of linen, but layers of papyrus. Further examination revealed something even more exciting. On some of the papyri, traces of Greek writing were visible. He also noted that

in the earliest

When Petrie examined the cartonnages found on the mummies of Gurob, he found, to his surprise, that the cartonnages were not made from layers of linen, but layers of papyrus. Further examination revealed something even more exciting. On some of the papyri, traces of Greek writing were visible. He also noted that

in the earliest  examples, the papyrus sheets had been stuck together using glue, but on later examples, this practice had been abandoned. Fortunately, most of the cartonnages, from the thirty or so mummies he recovered from Gurob, were of the unglued variety. This was fortunate, because insects found the glue very attractive. They would tunnel their way through the various layers of papyrus devouring the glue and in the end, leaving behind a thin shell of fragile unsupported stucco.

examples, the papyrus sheets had been stuck together using glue, but on later examples, this practice had been abandoned. Fortunately, most of the cartonnages, from the thirty or so mummies he recovered from Gurob, were of the unglued variety. This was fortunate, because insects found the glue very attractive. They would tunnel their way through the various layers of papyrus devouring the glue and in the end, leaving behind a thin shell of fragile unsupported stucco.

The next task Petrie faced, was to extract the papyri from the cartonnages. After much experimentation, mostly involving soaking the cartonnage in water for varying lengths of time, he was successful in extracting the papyrus sheets. Later, a treatment using steam and chemicals was used. Most of the papyri he recovered were very fragmentary and where the writing had been in contact with the stucco, the writing had been erased by chemical reaction with the lime in the stucco.

Shortly after, Petrie returned home to England, in the summer of 1890, he turned the papyri he had recovered at Gurob over to the Rev. Archibald Henry Sayce, an Oriental/Assyrian scholar at Oxford University. Sayce, along with Sir John Pentland Mahaffy, a Ptolemaic history scholar, would study, translate and eventually publish these papyri, now known as the "Flinders Petrie Papyri." This group of papyri proved to be of great interest, for they represented some of the oldest Greek manuscripts known up to that time. The papyri ranged in date from about 250 B.C.E to 220 B.C.E. and were mostly an assortment of legal and official documents, wills, official correspondences, accounts and private letters. However, the most exciting finds were those of literary works. These included: fragments containing the Phaedo of Plato, lost portions of the last act of Euripides play, Antiope and even fragments from the Iliad of Homer. These finds were big news at the time and fascinated the public. They also, opened the eyes of other Egyptologists to a previously untapped source of papyri. Petrie, however, was not the first to discover this fact. Sixty years earlier, Giuseppi Passalaqua, a collector and the first curator of the Berlin Museum Egyptian collections, had noted that mummy cartonnage was sometimes made from papyrus manuscripts.

Mummy cartonnage made from papyri would be recovered from other sites throughout Egypt.

Reusing waste-papyrus, instead of linen, to manufacture cartonnage became a common practice during the Ptolemaic Period.

The source for the large quantities of papyri used to manufacture cartonnages

was primarily discarded documents from government or official archives. The practice of making cartonnage continued through the Roman period.

During the later Roman period as the style of mummy decoration changed, linen

again would become the preferred medium for making cartonnage due to a need to

create thicker and more stable pieces (especially, for the head pieces).

Though, it is not unusual to find cartonnage constructed from mixed layers of linen and

papyrus or with outer layers of linen and an inner core of papyrus. The papyri which have been recovered from mummy cartonnages are not all exclusively written in

Greek. Demotic and Hieratic papyri have also been found.

linen, to manufacture cartonnage became a common practice during the Ptolemaic Period.

The source for the large quantities of papyri used to manufacture cartonnages

was primarily discarded documents from government or official archives. The practice of making cartonnage continued through the Roman period.

During the later Roman period as the style of mummy decoration changed, linen

again would become the preferred medium for making cartonnage due to a need to

create thicker and more stable pieces (especially, for the head pieces).

Though, it is not unusual to find cartonnage constructed from mixed layers of linen and

papyrus or with outer layers of linen and an inner core of papyrus. The papyri which have been recovered from mummy cartonnages are not all exclusively written in

Greek. Demotic and Hieratic papyri have also been found.

The process of recovering papyri from cartonnage has improved since Petrie’s

day, though still somewhat trial-and-error. More recently, various acids, enzymes and steam baths

were used to extract the papyri.  Unfortunately, all of these methods destroy the decorative stucco layer of the cartonnage and present a dilemma. Is it worth destroying a beautifully decorated cartonnage panel

or mummy mask to recover an ancient manuscript of unknown value to science?

Fortunately, new recovery techniques have been developed which are less destructive and leave the stucco layer intact.

Unfortunately, all of these methods destroy the decorative stucco layer of the cartonnage and present a dilemma. Is it worth destroying a beautifully decorated cartonnage panel

or mummy mask to recover an ancient manuscript of unknown value to science?

Fortunately, new recovery techniques have been developed which are less destructive and leave the stucco layer intact.

Working with papyri recovered from cartonnage can be very challenging.

The researcher is sometimes faced with having to reconstruct a manuscript from

multiple and often very fragmentary pieces. When making

cartonnage, the papyri were often cut or broken into strips or to whatever shape

piece was needed. It is not unknown for sections of a large papyrus

roll to have been broken up and used to make the cartonnages used on separate

mummies. Transcribing and translating the texts recovered from cartonnage

papyri presents another set of challenges. Some recovered texts are in

beautiful condition while others have suffered greatly from the manufacturing and/or

the recovery process. The ink used to write

the text can be water soluble. The texts on the papyrus are sometimes faded (washed off)

and very difficult to read. Further complicating things, the ink sometimes gets transferred or bleeds onto adjacent

layers. This can leave overlapping writing or reversed (mirror image) texts on the

recovered pieces.

needed. It is not unknown for sections of a large papyrus

roll to have been broken up and used to make the cartonnages used on separate

mummies. Transcribing and translating the texts recovered from cartonnage

papyri presents another set of challenges. Some recovered texts are in

beautiful condition while others have suffered greatly from the manufacturing and/or

the recovery process. The ink used to write

the text can be water soluble. The texts on the papyrus are sometimes faded (washed off)

and very difficult to read. Further complicating things, the ink sometimes gets transferred or bleeds onto adjacent

layers. This can leave overlapping writing or reversed (mirror image) texts on the

recovered pieces.

We owe a great debt of thanks to the ancient Egyptian undertakers. Their reuse of waste-papyrus to make cartonnage has provided us with a wonderful window into many aspects of life in Egypt and rescued a few classical works from oblivion.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Baikie, James Egyptian Papyri and Papyrus-Hunting. London, The Religious Tract Society (1925).

- Bagnall, Roger S. Reading Papyri, Writing Ancient History. New York, Routledge Press (1995).

- Bell, H. Idris Egypt from Alexander the Great to the Arab Conquest. Oxford, Clarenden Press (1948).

- D'Auria, Sue, Peter Lacovara and Catherine H. Roehring Mummies & Magic, The Funerary Arts of Ancient Egypt. Museum of Fine Arts Boston / Dallas Museum of Art (1988, 1992 reprint).

- Deuel, Leo Testaments of Time. New York, Alfred A. Knof (1965).

- Kenyon, Frederic G. The Palaeography of Greek Papyri Kessinger Publishing (1898, reprint 2007)

- Mason, Edward G. "Greek Papyri In Egyptian Tombs," The Dial. Chicago, A. C. McClurg & Co. (June 1892) Vol XIII pages 49-50.

- Parkinson, Richard and Stephen Quirke Egyptian Bookshelf: Papyrus. Austin, University of Texas Press (1995).

- Prestman, P.W. The New Paprological Primer (5th edition). New York, E.J. Brill (1990).

Related links

The University of of Helsinki in Finland has produced a Mummy Cartonnage Conservation video showing how the papyri are extracted while preserving the painted cartonnage decorations.

Digital Egypt for Universities from the University College London has a variety images and information about mummy cartonnage and related subjects.